Half-way through of Turn of the Tide, privileged Margaret Kendall learns that the mill supporting her privileged life illegally employs underage children. The story resumes the morning after the automobile bumps little Maggie.

Margaret asks Betty, the housemaid, if she knew of a “Maggie… one of the mill people’s children,” and gets a terse, negative reply. She approaches Frank Spencer in his office and confronts him about the night shift, and he explains:

“Why, of course. Other mills run nights; why shouldn’t ours? They expect it, Margaret. Besides, they are paid for it. Come, come, dear girl, just look at it sensibly. Why, it’s the night work that helps to swell your dividends.”

Margaret gives Frank a wad of bills and asks him to find Maggie and give the cash to her. Frank and Della worry that Margaret may become “morbid” about the mill workers and hope that the “nice” visitors will distract her with games and picnics.

The next day, we meet Bobby McGinnis who has become an educated and responsible adult. In Cross Currents, Bobby rescued five-year old Margaret from the city streets. In the early chapters of Turn of the Tide he helped nine-year-old Margaret to write a contract to protect her mother. He and Margaret have since lost touch, and Bobby has not disclosed his nearby presence to Margaret, although he has observed her from afar. He has (conveniently) worked at Spencers’ factory for a dozen years, but Frank and Ned Spencer are unaware that Bobby has a connection to Margaret.

On a cold September morning, Bobby encounters Nellie Magoon in the street. Plainly sickly, she lies about her age, knowing that she will be punished if it is discovered that she is only eleven. Bobby lets her continue on her way home, but confronts Ned Spencer, who is on his way to Frank’s office. Ned enters Frank’s office and says:

“McGinnis is on the war-path again.”

Frank smiled.

“So? What’s up now?”

“Oh, same old thing—children working under age.”

But Frank defends Bobby:

“He stands between me and the hands like a strong tower, and takes any amount of responsibility off my shoulders. You’ll see for yourself when you’ve been here longer. The hands like him, and will do anything for him. That’s why I put up with some of his notions.”

The Spencers discuss underage employees, which they see as maddeningly common in the U.S. and, seemingly, impossible to stop. The Spencer brothers deplore the intense competition that required low pay and long hours. They also blame greedy parents. “Good heavens, Frank… as if ’twas our fault that they lie so about the kids’ ages! They’d put a babe in arms at the frames if they could.” Many immigrant children and rural southerners had no birth records, and poor families who needed paper proof of age were prey to counterfeiters.

EDITOR’S COMMENT: Eleanor Porter’s account of the brothers’ conversation shows the complications faced by reformers at that time. Eleanor does not depict the mill owners as scoundrels, yet the conditions that prevailed at the time must have infuriated her.

Depending on the work, children were cheaper to pay, easier to boss and readily trainable. They were more dexterous. They did not get drunk. A child needed only routine supervision because misconduct at work was penalized twice — by docked pay at work and by punishment at home. The biggest drawback to employing youngsters was that they were injured more frequently, and their injuries were more serious. Amputations were common. Child workers grew up to become unhealthy, overworked, barely literate adults.

Despite New England’s zeal for childhood education, textile interests opposed public schools, and the region’s mills were very slow to reform. Southern mills were the most stubborn, however, and the aging textile empires of New England faced overwhelming competition from the South, where industry was virtually unregulated. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 1905, seventy-five percent of workers in North Carolina textile mills were under the age of fourteen. State laws were ineffective because they exempted abuses like longer hours, sped-up assembly lines and relaxed parental permission.

When Margaret confronted Frank in his office, she was not satisfied with his defense of the night shift at the mill. She laments the mill neighborhood’s poor housing and unclean streets. Part of her wants to believe that the factory slums are not as bad as they seemed on that day when Brandon drove there and that they may look more acceptable on a sunny day. On such a day, when the men are away, Margaret drives an automobile to the neighborhood.

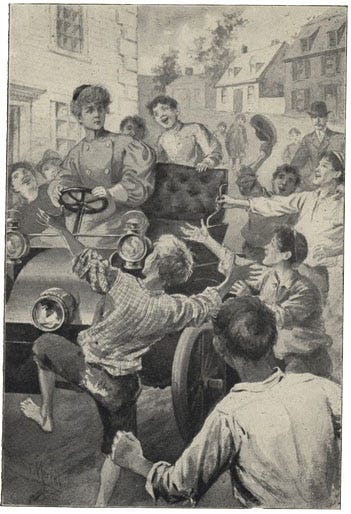

Her automobile is swarmed by mischievous boys, however, and she is rescued by Bobby McGinnis, who is still a stranger to her. In thanking him, Margaret recognizes her old friend, Bobby, and she exults in their reunion. As they part, Margaret tells Bobby that he is always welcome at Hilcrest. Bobby demurs, but she disregards his warning that “Bobby McGinnis is not on Hilcrest’s calling list.”

When Margaret reports her renewed friendship with Bobby McGinnis to the family, they are shocked. Della Meridith and the Spencer brothers are unhappy at the improbable bond between Bobby and Margaret, and that she will welcome him as a guest at Hilcrest. When weeks pass and Bobby does not visit, Della observes that this shows “some sense” on the millworker’s part, but Margaret is not pleased.

A month later, on an October day, Nellie Magoon, the underage mill girl, calls on Margaret Kendall at Hilcrest with a message from Mrs. Durgin.

“She said, ‘Tell her Patty is in trouble an’ wants ter see Mag of the Alley,’” murmured the child, as if reciting a lesson.

“‘Patty’? ‘Patty’? Not Patty Murphy!” cried Miss Kendall, starting forward and grasping the child’s arm.

Margaret takes a grand coach and team to the cottage. The coach and team park outside the dilapidated college and Margaret reunites with Patty Murphy, her Alley housemate.

“Patty—it is Patty!” cried an eager voice, and Mrs. Durgin found herself looking into the well-remembered blue eyes of the old-time Mag of the Alley.

They talk excitedly, and we learn that Patty works in the mill, and her absent husband, Sam Durgin, was an abusive drunk who scared away her sisters. Patty does not know where Arabella and Clarabella ended up. Margaret tells Patty how, after she left the Alley, she missed her friends, but was distracted: “[T]hey surrounded me with all sorts of beautiful, interesting things, and did everything in the world to make me happy… But I think I never quite forgot.”

Margaret asks Frank Spencer how to fix up the old cottage where Patty lives. Frank provides materials and labor, but Margaret supervises. She provides Patty’s family with food and medicine. There is a poignant moment when Margaret is playing with litte Maggie

“And how old are you now?” Margaret would laughingly ask each day, just to hear the prompt response:

“I’m ‘most five goin’ on six an’ I’ll be twelve ter-morrow.”

Margaret always chuckled over this retort and never tired of hearing it, until one day Patty sharply interfered.

“Don’t—please don’t! I can’t bear it when you don’t half know what it means.”

Patty explains that the Maggie had been taught the “twelve ter-morrow “reply as a cruel joke about underage children lying about their ages. Margaret is horrified to learn the extent of child labor at the mill. She again confronts Frank Spencer.

“Margaret, dear child, don’t!” he begged. “It breaks my heart to see you like this. You are carrying the whole world on those two frail shoulders of yours.”

“No, no, it’s not the whole world at all,” protested the girl. “It’s only a wee small part of it—and such a defenseless little part, too. It’s the children down at the mills.”

Frank assumes that she is helping Bobby McGinnis in one of his “pet schemes,” but Margaret retorts, “I have not seen him, indeed, since that first morning I met him.” She is encouraged to hear that Bobby might be sympathetic to her “practical” reforms, but disappointed that he has not called at Hilcrest. Margaret angrily tells Frank what she has learned about the treatment of mill children.

“But, my dear Margaret, I did not put them there. Their parents did it.”

“But you could refuse to take them.”

“Why should I?” he shrugged. “They would merely go into some other man’s mill.”

“But you don’t know the worst of it,” moaned the girl. “They’ve lied to you. They aren’t even twelve, some of them. They’re babies of nine and ten!”

Margaret bases her criticism on what Bobby McGinnis’ has told her, but Frank contends that she cannot comprehend the awful dimensions of the problem:

“Margaret, I beg of you to believe me when I say that you do not understand the matter at all. Those people are poor. They need the money. You would deprive some of the families of two-thirds of their means of support if you took away what the children earn… [D]on’t, for heaven’s sake, let your heart run away with your head when it comes to the business part of it!”

“Business!—with babies nine years old!”

“…Margaret, don’t look at me as if you thought I was a fiend incarnate. I regret this sort of thing as much as you do. Indeed I do. But my hands are tied. I am simply a part of a great machine—a gigantic system, and I must run my mills as other men do… Come, please don’t let us talk of this thing any more to-night.

She agrees to leave the office with the words:

“Very well, I will go,” sighed Margaret, rising wearily to her feet. “But I can’t forget it. There must be some way out of it. There must be some way out of it—somehow—some time.”

Eleanor Porter uses the adjective “restless” to describe Margaret’s mood when she is between challenges. Satisfied that she has remedied Patty’s situation, Margaret is again “restless.” After her quarrel with Frank, she mopes around Hilcrest. Ned Spencer takes the opportunity to more seriously court her, and she fends him off, but guiltily because he is obviously hurt. Romance is not on her mind. Margaret realizes that her impressions of the mill are only second-hand. Perhaps, she is naive. She has not actually witnessed underaged children working at the Spencer mills. Margaret remembers “McGinnis’ pet schemes” and she writes a letter to Bobby:

“Will you come, please, to see me to-morrow night? I want to ask some questions about the children at the mills.”

Della is scandalized that Margaret has invited McGinnis to Hilcrest. She begs Margaret not to “make any foolish promises” and retreats to her bedroom. Bobby McGinnis arrives, but : “The young man had not come to pay a visit: he was an employee who had obeyed the command of one in authority.” He is formal and unsmiling. He eventually thaws when Margaret explains that she wants to see children at work and also see their homes . She tells him, “[B]efore help can be effectual, or even given at all, the conditions must be understood. That is what I mean to do—understand the conditions.” Bobby warms to the topic and “he knew his subject, and his heart was in it.”

Before she and Bobby tour the factory, Margaret argues with Della and meets with Frank. Della tells Margaret not to “ mix yourself up personally with such people” and to trust the Women’s Guild. Margaret replies:

“But don’t you see that they can’t reach the seat of the trouble?… Why, even that money which I intended for little Maggie went into a general fund, and never reached its specified destination.”

Della takes up the argument with her brother. Frank finally tells Della that Margaret “must be allowed to do as she likes in this matter…

We must not make her quite—hate us!” His voice broke over the last two words, and he was gone before Mrs. Merideth could make any reply.

Frank Spencer assigns Bobby McGinnis to guide Margaret on her inspection. They meet in Frank’s office, and Frank’s formal decency disarms Margaret. As she and Bobby leave his office she turned back to thank him.

She thought she knew just how much the calm acceptance of the situation had cost him, and she appreciated his unflinching determination to give her actions the sanction of his apparent consent. It was for this that she gave him the grateful glance—but he did not see it. His head was turned away

We are two thirds of the way through The Turn of the Tide. NEXT is Part Three

Eleanor put most of the action in the the last third of the book. Margaret is about to tour the factory with Bobby, to whom she is engaged. She has yet to develop her Mill House. Nor has she reunited Patty with Arabelle and Clarabelle. And, there’s a big fire at the mill and a happy ending still to come.

Illustrations: Gutenberg.com edition of Turn of the Tide and Library of Congress’ collection of Hines photos and Child Labor posters. (Lewis Hine (1874-1940) documented underage workers throughout the US in the Progressive Era.)

Copyright © Jim McIntosh 2025