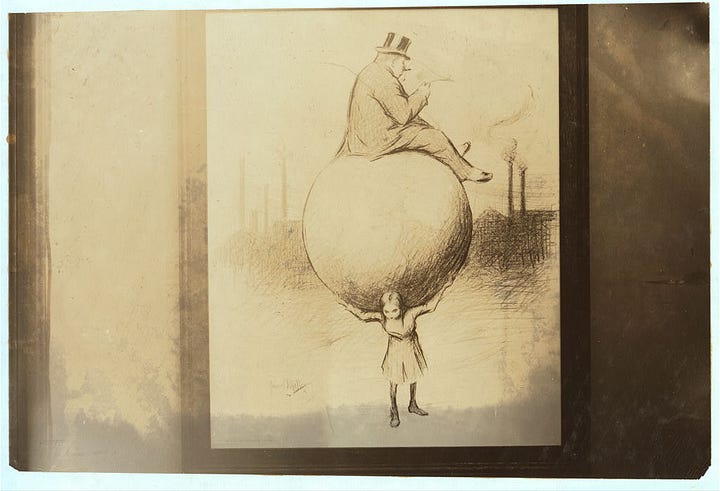

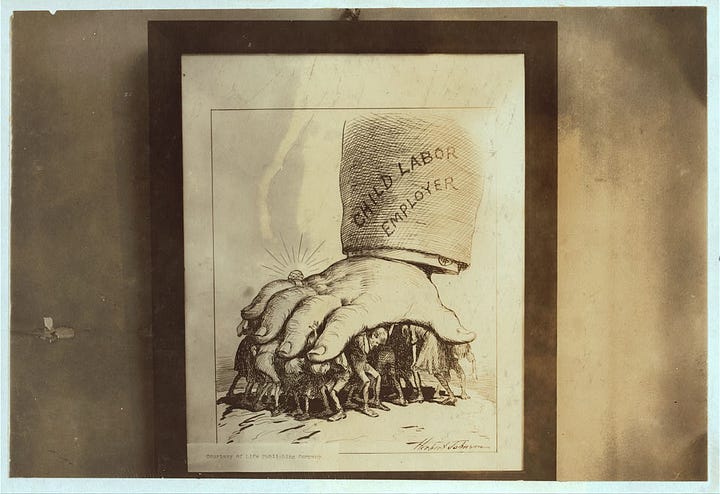

Published in 1908, Eleanor Porter’s second book, The Turn of the Tide, is forty-one chapters long (about 300 pages) and is a sequel to Cross Currents. Most of the book tells of how privileged Margaret Kendall, as an adult, draws on her childhood ordeal and asserts herself to confront the evil of underage labor.

Margaret remains a child for only eight weeks (90 pages) until her mother marries Dr. Spencer in Chapter XII. Suddenly, in the next chapter, the story jumps ahead to when Margaret is twenty-three years old, college-educated, upper-class and orphaned. Her family owns a mill. She discovers the mill employs underage workers and is moved to address the evil practice. She re-connects with her friends from the Alley, becomes an activist, begins a shelter, and decides on a husband.

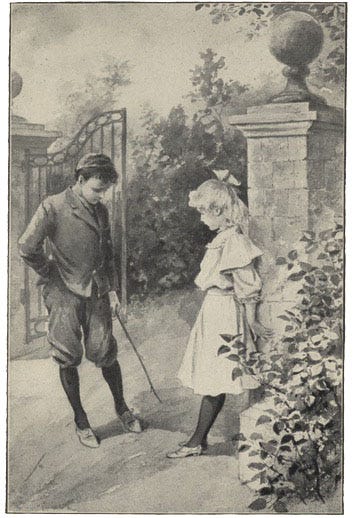

The Turn of the Tide begins on the same day that Cross Currents concludes: little Margaret Kendall’s homecoming at Five Oaks, the family estate in Houghtonsville. Margaret, was lost in the New York slums at age five. Now, nine years old and in the embrace of her mother, Amy Kendall and Dr. Harry Spencer, the unschooled girl struggles to learn the manners, speech and conduct of an upper-class young lady. Proper behavior in society, however, goes against the code of the Alley. Her challenge is to shed the role as rude and scrappy “Mag of the Alley,” but not lose the resilience and empathy the ordeal has taught her.

“Just there lies the greatest problem of all. The one creed of her life is to ‘divvy up,’ and how I’m going to teach her ordinary ideas of living without shattering all her faith in me I don’t know.” — Mrs. Amy Kendall

Margaret cannot enjoy her good fortune at Five Oaks because she feels she should share it. She protests that her city companions subsisted in squalor, and that makes it wrong for her to live on an estate with only her mother and four servants. She proposes that her friends come to live at Five Oaks. Taken aback, her mother stalls the girl. Margaret’s manners remain crude. She beats up a bully who is tormenting a cat. She uses language like “ain’t” and “shucks.” She consults with Bobby McGinnis, now an office boy at a nearby law office. She also retains bad memories. For example: her only experience of “husbands” were brutes who abused their wives, thus, Margaret makes a scene when her mother becomes engaged to marry Doctor Harry Spencer. She frets until Bobby writes a a contract that forbids the doctor from beating her mother. Margaret makes the doctor sign it. The adults are amused by the gesture but also recognize the depth of Margaret’s emotional distress.

Margaret begins to face her problem when six of her Alley friends visit Five Oaks and she finds herself becoming impatient with them. Her mother allows Margaret to invite Arabella, Clarabella and Patty Murphy, plus Mary, and Peter Whalen and their father Tom. Their reunion is happy. With generous meals, sunshine and outdoor romps the children grow healthy in the wholesome surroundings.

After a short time, however, Margaret recognizes that Five Oaks does not improve her guests’s unrefined speech or manners. Worse, she, herself, has gone back to speaking the slang of the Alley. She is angry at herself for being angry at them. She breaks down and tells Bobby that she wants the six visitors to leave, but also insists that the code of the Alley dictates that she should “divvy up.” Bobby differs. She did not promise that they could live at Five Oaks permanently:

“Shucks!” rejoined Bobby, his face clearing. “Then what ye cryin’ ‘bout? You ain’t bound by no contract. You don’t have ter divvy up.”

“But I ought to divvy up.”

“Pooh! ‘Course ye hadn’t,” scoffed Bobby. “Hain’t folks got a right ter have their own things?”Margaret frowned doubtfully.

“I don’t know,” she began with some hesitation.

Finally, Margaret and her mother move the poor families from the Alley to a country cottage with a garden, but they were not happy in the quiet neighborhood. By September, they all move back to the Alley. Mrs. Kendall leases new living spaces for them and arranges for food. Margaret, hurt by her friends’ rejection, becomes despondent.

In September, Margaret and her mother vacation for a month in the White Mountains. Then, Margaret enters Elmhurst, a boarding school in the Berkshires, because “[Her mother] particularly wished Margaret to have the companionship of happy, well-bred girls of her own age” and, also to distance Margaret from Bobby McGinnis. The school staff is ordered to speak only of beauty and goodness. She does not return to Five Oaks until Christmas Eve, also the day before her mother will marry Dr. Harry Spencer.

Margaret now is thrilled by the idea of marriage. After the “happy, well-bred” girls at Elmhurst learned of her mother’s betrothal, they convinced her that husbands were quite desirable. They shared their story books: “The girls all had them, and each book was full of fair ladies and brave knights, and of beautiful princesses who married the king—and who wanted to marry him, too, and who would have felt very badly if they could not have married him!”

During the celebrations, Margaret privately talks with Bobby McGinnis who came uninvited. His slang talk now contrasts with her proper speech, and he is aware of their growing social distance. Suddenly Bobby proposes marriage. “Mebbe when we’re grown up we’ll get married, too,” he blurted out, saying the one thing he had intended not to say. Suffused with the joy of the occasion, Margaret replies hastily with “Could we?” and adds that they will see Europe, to which Bobby hesitatingly agrees. Satisfied, she returns to the reception, and Bobby, still uncertain, sneaks out. Margaret tells her puzzled mother that she and Bobby will marry and travel.

And, Chapter XI ends. So does the story of Margaret’s childhood. The Turn of the Tide resumes Margaret’s story thirteen years later in Chapter XII.

Chapter XII begins in the dining room of Hilcrest, the Spencer family mansion. Two surviving Spencer brothers and their sister discuss the impending arrival of a young woman whom they do not know. We learn that their eldest brother was Doctor Harry Spencer, but that he and Margaret’s mother perished in a railroad mishap soon after they wed.

Before succumbing, however, Harry Spencer assigned the guardianship of Margaret to his younger brother, Frank, who was only twenty years old. Frank Spencer since has met Margaret only very briefly. Now, thirty-three years old, Frank manages the Spencer & Spencer family mills. In the Hilcrest (EHP’s spelling) living room, he tells Margaret’s story to his brother, 24-year-old brother Ned Spencer, and his older sister Della Merideth (EHP’s spelling). Eleanor Porter introduces Della’s household in a tightly-written paragraph:

For fifteen years now she had been mistress of Hilcrest, ever since her mother had died, in fact. Widowed herself at twenty-two after a year of married life, and the only daughter in a family of four children, she had been like a second mother to her two younger brothers. Harry, the eldest brother, had early left the home roof to study medicine. Frank, barely twenty when his brother Harry lost his life, had even then pleased his father by electing the mills as his life-work. And now, five years after that father’s death, Ned was sharing his brother Frank’s care and responsibility in keeping the great wheels turning and the great chimneys smoking in the town below.

Della recalls that illness had prevented the Spencers from attending Harry’s wedding, and that is why they never met Margaret as a child. She asks Frank about the girl’s past, and, when Mrs. Merideth hears of Margaret’s passion for “sharing all she had” with “ragamuffins,” the news alarms her.

“Dear me!” she sighed. “I do hope the child is well over those notions. I shouldn’t want her to mix up here with the mill people. I never did quite like those settlement women, anyway, and only think what might happen with one in one’s own family!”

But, when Della meets her at the train station, Margaret is dressed like a lady and possesses “the most wonderful eyes she had ever seen.” The ladies are passengers of Frank Spencer who drives a large touring car. His route to Hilcrest avoids the factories and worker’s tenements, and Margaret seems oblivious to their existence. Indeed, in the days that follow, Della becomes her happy companion and Margaret is content with music, golf and motoring. Ned flirts clumsily with her, but she deflects him with her charm.

After a month, however, Della and Frank detect a restlessness in Margaret, and Della resolves to invite “some nice people up for a week or two… to liven things up.” Frank is more perceptive. He sees Margaret’s restlessness as an internal struggle, an effort to confront something within herself. “I believe her coming here was merely another effort on her part to get away from this something—this something that while within herself, perhaps, is none the less pursuing her, and making her restless and unhappy.”

Margaret’s inner turmoil surfaces while the “nice people” visit Hilcrest. She is riding home from a picnic at a lake with a man named Brandon. He makes a wrong turn and exposes Margaret to the sight of homebound workers from the Spencer and Spencer mills. She learns they are finishing work on the day-shift.

“The day-shift?”

“Yes; the hands who work days, you know.”

“But don’t they all work—days?”

Brandon laughed.

“Hardly!”

“You mean, they work nights?”

Brandon tells Margaret how the night shift is a “special pet” of Frank Spenser and responsible for the mill’s prosperity, but the subject is dropped when Brandon must swerve to avoid a child on a bicycle. He notices a horrified expression on Margaret’s face and drives faster — until he bumps a little girl to the ground, and he stops the car to attend to the five-year-old victim, whose name, they learn, is Maggie. Margaret impulsively gives the girl a handful of cash, and they flee.

Maggie’s mother, Mrs. Durgin, takes the un-hurt girl into “a shabby-looking cottage” and is awed at her fistful of money. A limping woman named Mrs. Magoon enters. Mrs. Magoon is pleased that her eleven-year-old daughter Nellie is at work, even though she has a bad cough. Mrs. Magoon complains bitterly about wealthy people in automobiles, but Mrs. Durgin allows that not all wealthy people are rude and selfish. She tells of a girl she knew who turned out to be very wealthy but was still kind. It will soon be disclosed that Mrs. Durgin is Patty Murphy from the Alley. Margaret vows to improve the lot of the millworkers.

We have reached the half-way mark of Turn of the Tide.

The story continues with a cast of characters previously populating Cross Currents. Margaret, impatient with established charities, helps the victims directly.

NEXT — The Turn of the Tide [PART TWO]

Illustrations: Gutenberg.com edition of Turn of the Tide and Library of Congress’ collection of Hine photos. (Lewis Hine (1874-1940) documented underage workers throughout the US in the Progressive Era.)

Copyright © Jim McIntosh 2025

Pollyanna has so dominated Porter's work that it's easy to ignore the fact that she wrote about 14 other novels and quite a few short stories. Which of her other works do you think is most worthwhile to read? Is it this one?