Part One

" Sure, an' it's a swate song yer a-singin'," muttered Mrs. Whalen at last. "Sing it agin, kids! “

— Cross Currents Chapter 18

With the publication of Cross Currents (The Story of Margaret) in 1907, Eleanor, the Musician became Eleanor, the Novelist, the occupation she followed for the rest of her life. Her change in career was partly due to a historic change in the world of music.

EHP was a professional musician in 1900 when she moved to Boston and began writing short stories. It was a significant time: the Gramophone company had been founded in 1898 in England and the first recorded disks of opera music (Enrico Caruso) were made in 1902. The heretofore rarified world of great music and famous performers would visit American parlors by way of a wooden box attached to a big metal horn. Up until then, few Americans regularly heard music performed by professionals. They needed to hire a trained musician like Eleanor to hear good music, while ordinary households had “musicians-of-necessity” — amateurs who could pick out a tune on the violin, accordion, piano, etc. If the performance was competent, it was called “parlor music,” which was Eleanor’s profession. The way things turned out, she was wise to change careers.

Mrs. Porter’s new career would eventually birth unmusical Pollyanna, who dodged piano lessons but amused and inspired the entire world. In the thirteen other novels that Eleanor wrote, five have protagonists who are aspiring professional musicians, and seven more feature amateur pianists and singers as important characters. Other novelists have put musicians in their stories, but not so often and not with such fond and accurate evocations!

Cross Currents

The Story of Margaret

In Cross Currents, five-year-old Margaret Kendall, the daughter of a rich, pretty widow, is cast into the slums to live with the humble Whalen family and work in sweat shops. The only relief from the grim toil and hunger is a week at Mont-Lawn, a Christian fresh air camp where Margaret and the Whalen children learn to sing hymns. When they return to the tenement, Margaret coaxes them to sing Grace at dinner.

Patty and the twins were just about to fall upon their share of the bread and mush when Maggie raised a warning hand.

" Sh-hh! Have ye forgot? " she demanded. " We didn't sing yet."

" Sing! Do ye reckon we could here? — jest us? " cried Patty.

" Sure!" declared Maggie. And she fearlessly started the song.

Over across the room Mrs. Whalen stopped scolding, and her husband stopped swearing. Even the children forgot to quarrel over their breakfast ; and as the last sweet "God is great, and God is good" died into silence, there was a breathless hush in the room.

"Sure, an' it's a swate song yer a-singin'," muttered Mrs. Whalen at last. "Sing it agin, kids!”

That was but the beginning. Before the week was out the landlady's children themselves had learned the song, and "Grace before Meat" became a regular prelude to every meal in the Whalen home. Nor was this all. There were other songs and hymns that Maggie remembered, and in a wonderfully short time she had half the children of the neighborhood organized into a chorus that met every night at sunset for a "song service."

In this passage, EHP shows how Margaret’s desire to sing hymns reveals how mischievous“Mag of the Alley” alleviates misery with music. Margaret endures her plight until she is rescued by her mother’s beau, Dr. Spenser, and returned home.

The Turn of the Tide

The Story of How Margaret Solved Her Problem

In Eleanor Porter’s second published novel, The Turn of the Tide, Margaret’s story is continued with complications. The 1908 book begins when Maggie Kendall returns to her mother at age nine. She is discomfited by the family mansion’s opulence and wants to share her home with her slum friends. But, suddenly, the story jumps ahead thirteen years, and, abruptly, Margaret is involved in an adult romance.

She falls in love with Dr. Spenser’s factory-owning brother. (Dr. Spenser and her mother have perished.) But, she learns that children are toiling in the very mills that are her own source of wealth so she is conscience-stricken and ambivalent toward her suitor. Her anxiety is resolved when she starts a settlement house for unfortunates and marries the industrialist (who promises to change abusive labor practices).

One way Margaret dramatizes her turmoil was in music:

Miss Kendall was restless that day. She rode and drove and sang and played, and won at golf and tennis; but behind it all was a feverish gayety that came sometimes perilously near to recklessness. Frank Spencer and his sister watched her with troubled eyes, and even Ned gave an anxious frown once or twice. Just before dinner Brandon came upon her alone in the music room where she was racing her fingers through the runs and trills of an impromptu at an almost impossible speed.

“If you take me motoring with you to-night, Miss Kendall,” he said whimsically, when the music had ceased with a crashing chord, “if you take me to-night, I shall make sure that the brakes are on my side of the car!”

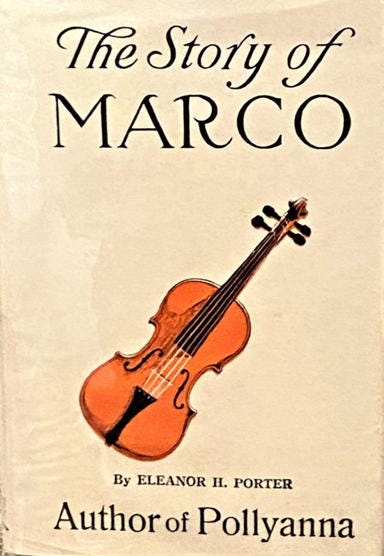

The Story of Marco

Eleanor had been writing almost ten years when she published The Story of Marco in 1911. Eleanor employed a Child Protagonist in her first three books. She was impatient with sanctimony and hypocrisy and used a child’s innocence to puncture vanity and pretensions. Child narrators can be critically observant and embarrassingly outspoken. They emerged in the 1830s with novels like Oliver Twist and they reigned into the 1900s with youngsters like Margaret, Pollyanna and Marco.

In her first three books, Eleanor Porter had established her familiar stock characters: widows, orphans, boy saviors, wise doctors, precocious children and handicapped persons of all ages. They usually live in New England and suffer from personal or societal ills. Their stories are sentimental and melodramatic, the kind that her readers expected and enjoyed. Also, her characters increasingly have music in their lives.

Marco’s story begins with his father missing, his mother dying and his sister Flossie kidnapped. He plays his violin in the streets for coins. Like Margaret, he shelters with a poor family in the slums and attends the fresh air camp Mont-Lawn. He slaves in a coal mine, gets sick and works for an itinerant organ grinder. He always plays “Lost on the Ocean Wave” — a song that Flossie would recognize. His genius is finally recognized by a wealthy patron, and he becomes Marco Covino, a world-famous violinist. By way of wonderful coincidences and by playing Flossie’s song, he is reunited with his sister for a very unexpected, happy ending.

To illuminate the paradox of an illiterate vagabond who shows surprising talent, Eleanor uses a composition from an opera.

“Who taught you to play like that, Marco?” she asked.

“Mumsey, first. After that I jest played. Then, two years ago, there was an old man what lived where we did, an'he played bang-up, he did—in orchestrys, an’ all that. He teached me pieces lots of ‘em, nicer’n mine, yeknow, like this." And there floated out into the room the first sweet tones of the ever-familiar, ever beautiful "Intermezzo" from “Cavalleria Rusticana.”

This passage describes the moment when Marco, the street urchin, is discovered by the Preston family who will sponsor him and send him to Europe for training. He plays the Intermezzo from the one-act opera “Cavalleria Rusticana.” by Pietro Mascagni. First performed in 1890 , when EHP herself was performing professionally, it is considered to be the most famous intermezzo in opera. At a little over three minutes in length, it denotes the passage of time and foreshadows tragedy. It was employed in films “Godfather III” and “Raging Bull.”

With support from the Prestons, Marco conquers Europe in a triumphant performance of Tchaikovsky in Berlin, Germany. As Signor Marco Covino he overcomes his shyness, perfects his performances and becomes an acclaimed international concert violinist. He returns to America and stays with the Preston’s and their adopted daughter, Florence:

The two young people were at the top of the house, practicing some new music. The beautiful room had always been a favorite with them both; and it had never seemed more lovely than it did to-day, with the last rays of the sun falling through the alcove window where the boy Marco had so long ago played his violin. In the new music now that he was playing, Marco had found a curious melody — a weird little phrase that made him stop abruptly.

“Why, how odd!”he murmured. “That is almost exactly like it."

“Like what?"

“A little tune that I used to play year sago."

“Perhaps it’s the same,” suggested the girl “It sounded almost familiar to me, too. I think I have heard it somewhere."

Of course, music unites Marco and Flossie for a happy ending. Nine years later, in 1916, EHP would publish Just David, another story about an orphan violinist who finds riches and fame. She writes more descriptively in the later book, conveying a performer’s emotions with mature depth and precision.

Following the publication of The Story of Marco, Miss Nellie Hodgman, singer and pianist, stayed close by the elbow (or ear) of Mrs. Eleanor Porter, storyteller and novelist. They next created Billy Neilson. Part Two of Glad Refrains will be about the Miss Billy books, a trilogy that depicts both amateur and professional musicians and immerses the reader in the cultural life of Boston’s gilded age.

Next: Glad Refrains II [Miss Billy Books]

Copyright © Jim McIntosh 2023

Sounds good, Jim.

You must be the premier expert on the works and music of Eleanor Porter. As a musician, did she play an instrument or simply sing? Just curious.

FYI, my Hidden History is recommended by the Shepherd book review this time around. And I think you had me send Hidden History to your friends, whose contractor has broken ground for their new house, right here in Oak Bluffs.

And also, FYI, I sent my last shipment of Dogtown books off to Gloucester. It had a remarkably long run of a quarter century, plus; now I can retire! Best in 2023, Tom