The years from the 1890s to the 1920s were the Progressive Era, when the nation aimed to correct inequities that resulted from industrialization and urbanization. Most of Eleanor Porter’s books depict characters who live in a fictional version of New England and they endorse Progressive causes.

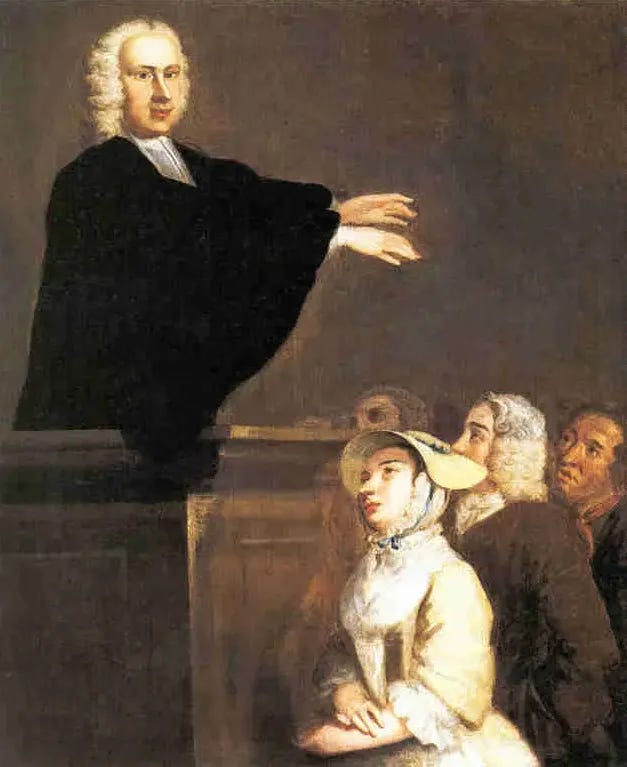

A Mayflower Descendant who heeded the Social Gospel, Eleanor Porter shared the New Englander’s impulse for reform, a propensity that dates back to her Puritan ancestors. In Pollyanna, she portrays Reverend Ford preaching from Puritan Jonathan Edwards’ 1741 “ Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” — until Pollyanna teaches him the Glad Game and tempers his sermonized scolding.

In the 1800s, this passion for reform fueled the Abolitionist movement which helped to define the Union’s role in the Civil War. Now, in the new century, Progressives sought reform of labor policy, social welfare, sanitation, etc., but at the top of their agenda was Temperance and Women’s Suffrage.

Both became law in 1919. The passage of the 18th Amendment enacted National Prohibition and the 19th Amendment granted women the vote.

Prohibition

Eleanor Porter’s novels never mention Prohibition. Except for her first three books, in which alcoholic fathers force children to work, they rarely depict drunkenness, and allude only to off -stage intoxication. Beverage alcohol is absent.

Eleanor’s attitude toward liquor formed when she grew up in Littleton, New Hampshire. In the late 1800s, Littleton, like most small towns in New England, had been pretty much “dry” since mid-century. Also, Maine and Vermont had enacted state-wide bans of alcohol in the 1850s (though enforcement was erratic), while New Hampshire law offered “local option prohibition” that banned the sale of alcohol but allowed local exemptions, such as for inns and apothecaries.

It seems temperance with local control fostered an attitude that habitual intoxication is a personal shortcoming and a family misfortune but not a national problem. Most of Eleanor’s fictional characters adopt a progressive cause as one of their winsome traits, but nobody advocates Temperance.

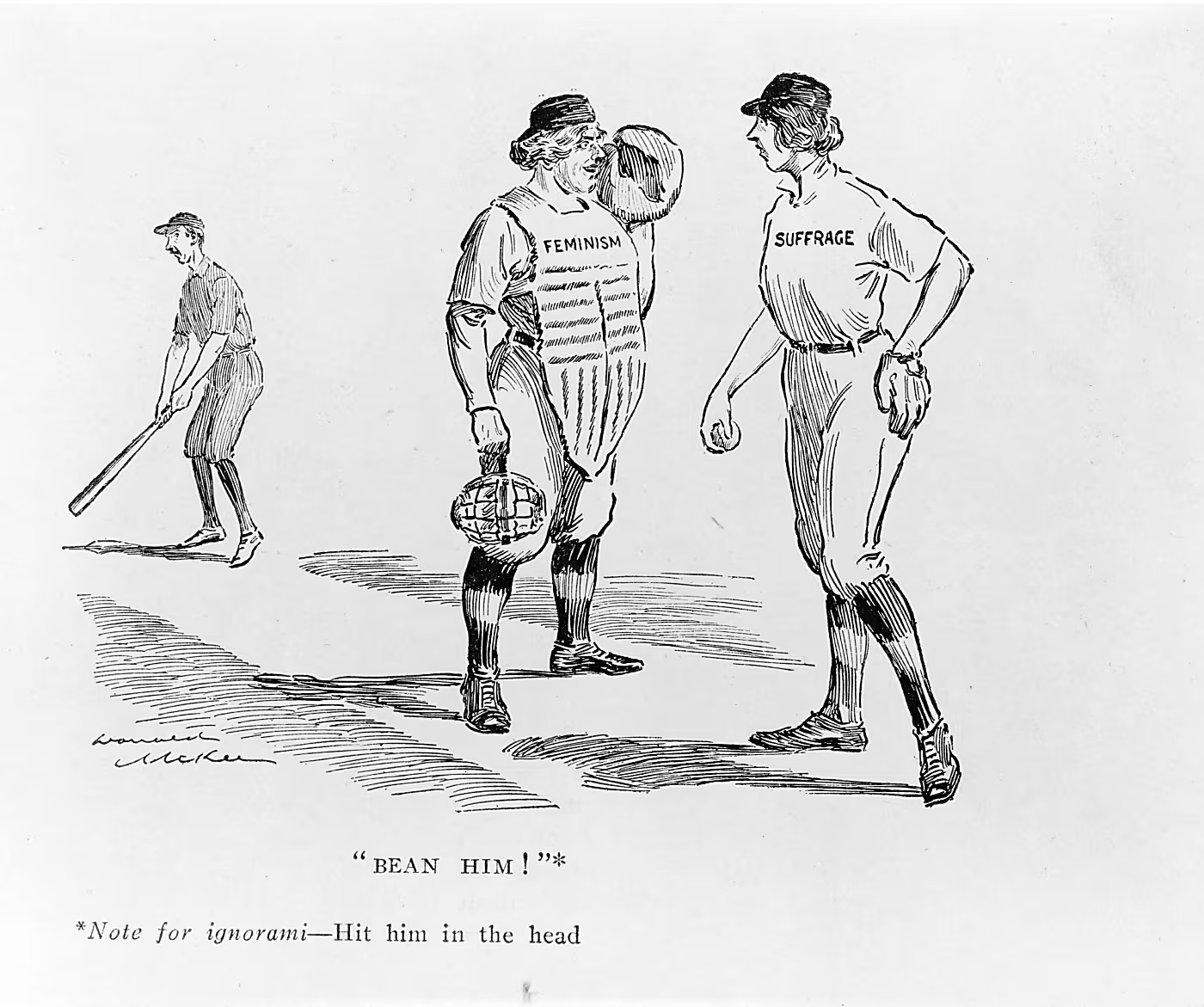

Women’s Suffrage

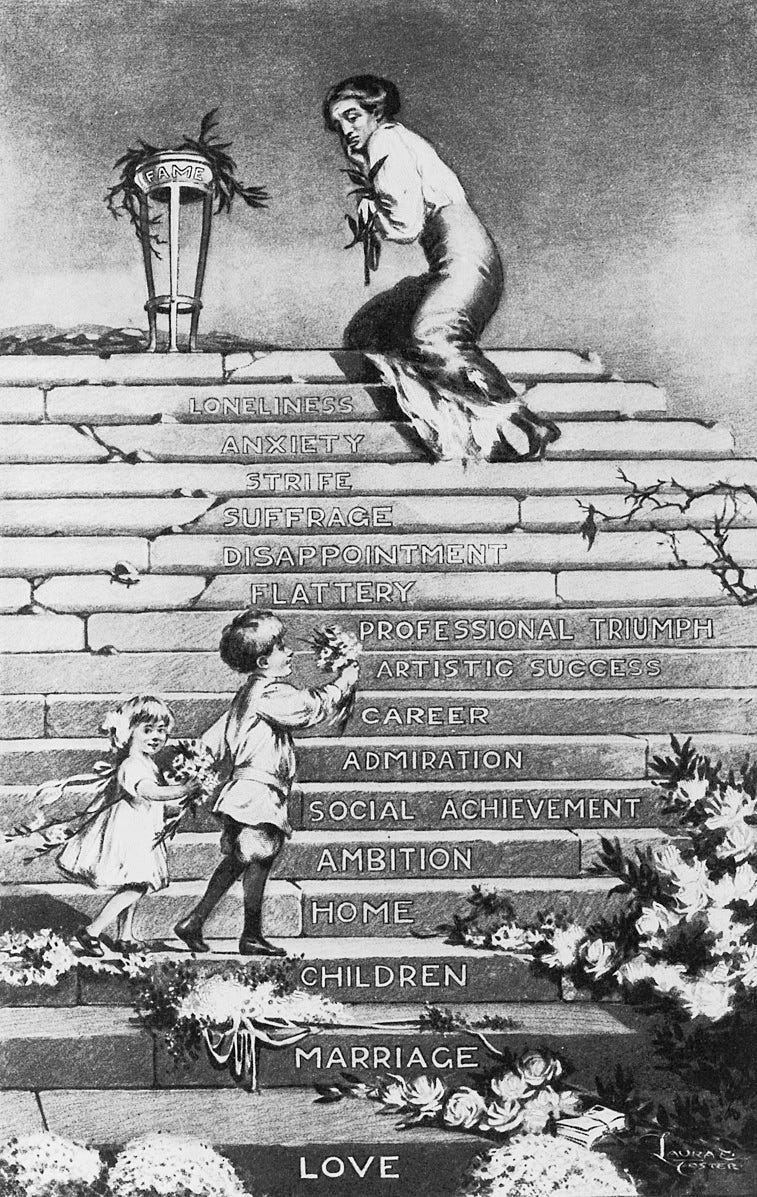

Eleanor Porter never mentions voting at all. Yet her fifteen books portray independent, gifted and intelligent New England women who, we assume, would support universal suffrage— unmarried protagonists like Miss Billy, Sister Sue and Pollyanna (in Pollyanna Grows Up). They never refer to suffrage. Did Eleanor oppose the franchise?

Most probably not, but to understand why she created no suffragist heroines, we must put conventional wisdom aside and think like a contemporary Cantabrigian. It is possible that most of Eleanor’s readers would be bored by a suffragist character.

Massachusetts women had already earned the right to vote in municipal elections in the 1870s. Their source of power had been child-rearing, and men were happy to cede the growing responsibility for state education to women. In Massachusetts, women dominated school boards. They wielded tax and budget power. State-wide they introduced and promoted reforms like “normal schools” to train teachers. Women served on legislative committees.

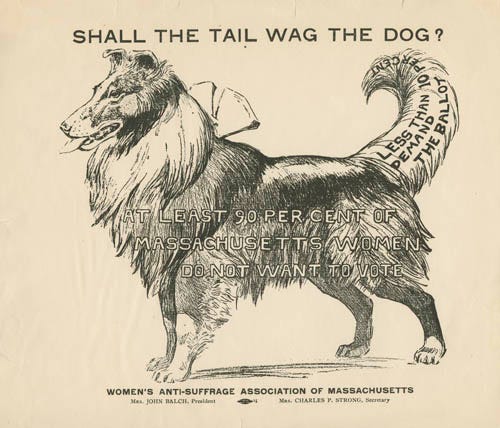

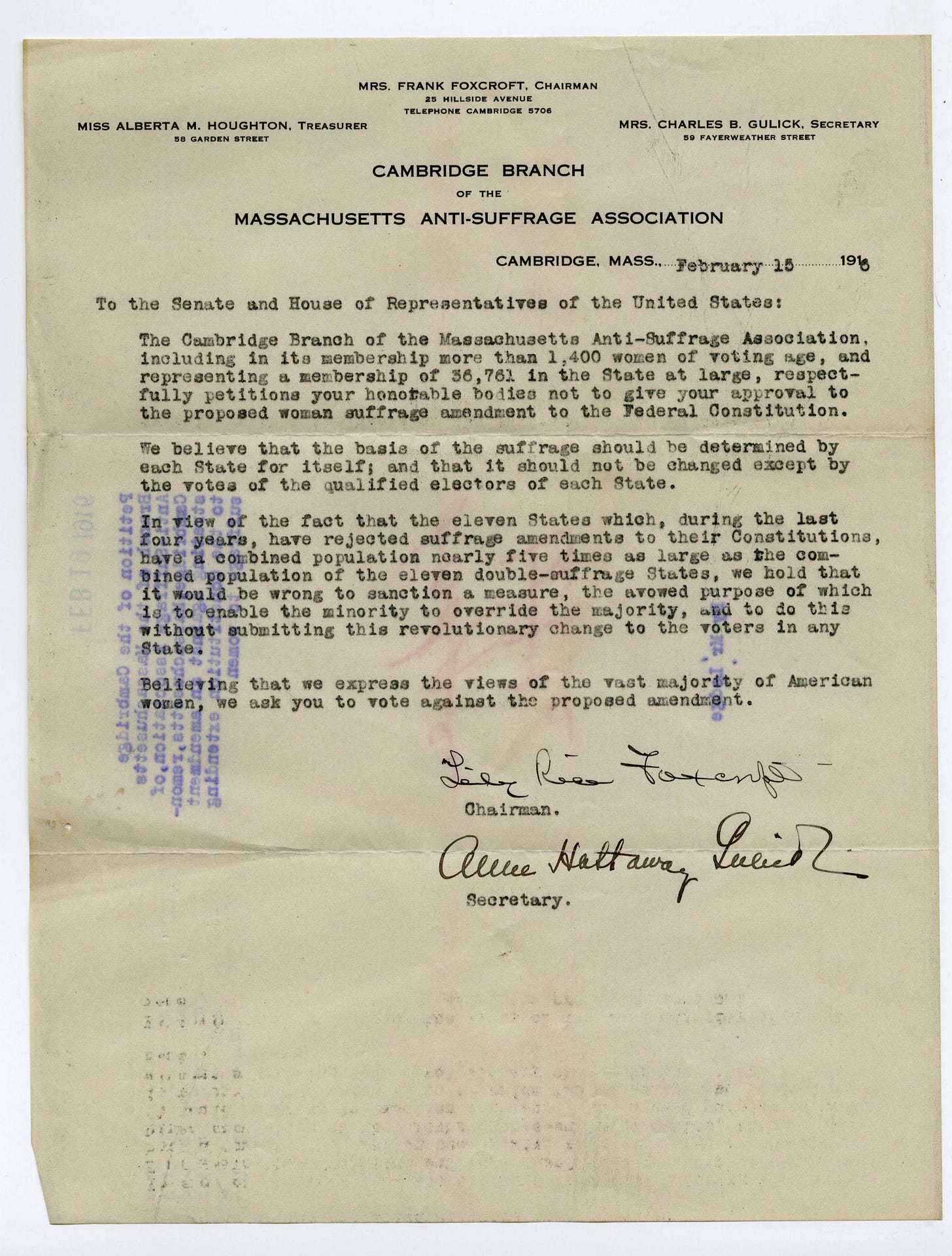

Suffragists strained to motivate them, but Bay State women had plenty of responsibility and were reluctant to take on more. The most active opposition to suffrage was mostly women. A large group of connected society women led the opposition in Massachusetts. They published a quarterly journal: The Remonstrance. It was difficult to persuade these ladies that they should care as much about “men’s politics” as they cared for the welfare of children.

To bring matters to a head, the suffragists called for a state-wide referendum in which women could vote. It was in 1895 and it was a disaster for the cause. One historian relates:

The only referendum for women only was held in Massachusetts in 1895, and only 4% of eligible women voted. Anti-suffragists had encouraged women to stay away from the polls, and the vast majority of them did. In fifty-seven towns, not a single woman voted for suffrage. Of those few votes that were actually cast, 96% were pro-suffrage. For many years afterward, suffrage leaders like Julia Ward Howe cited that 96% figure as a victory, but they never again asked for a referendum of women only.

— Joe Miller. Never A Fight of Woman Against Man: What Textbooks Don't Say about Women's Suffrage .The History Teacher, Vol. 48, No. 3 (May 2015), pp. 437-482 Published by: Society for History Education

Eleanor Porter’s silence on the issue of suffrage was not a political position. For a writer of escapist fiction it was best to avoid mentioning or even alluding to a controversy so divisive. Suffrage was not a cause that all readers would find relevant, and its advocacy might not appear an attractive trait, especially in Massachusetts.

I was reminded of the family in Eleanor’s novel, The Road to Understanding (1917), in which the rich husband liked classical music, but the bride liked ragtime music. For EHP, ragtime music was a sign of uncultivated taste and she implied that it appealed to a lower class. The Denbys separate while the wife becomes refined and attuned to her husband’s tastes. Years pass, and the Denbys re-unite for a happy ending, but…

Imagine Eleanor, the classical musician, realizing that her readers might actually like ragtime music. To craft a happy ending, EHP makes the husband finally (and implausibly) enjoy ragtime music — an unconvincing compromise.

Most of the time, EHP’s progressive notions are reforms that her genteel readers would endorse. The issue of suffrage was different. It divided families and communities, but unlike the Denbys and ragtime music, there could be no compromise.

Epilogue

Of course, Massachusetts suffragists did prevail. Circumstances changed. The number of women supporting suffrage multiplied after 1915, and reached a majority by 1919.

On June 25, 1919, Massachusetts was the eighth state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

Illustrations: Library of Congress, Needham, MA Women’s Club, NY Times, Palczewski Suffrage Postcard Archive.

Copyright © Jim McIntosh 2025